From the very beginning, chiropractic is based on the idea that when the spine and nervous system are not working together as they should, people do not adapt well. They do not sleep as well, recover as well, or handle life’s stress nearly as well. Spinal subluxation is the word we have used to describe that constellation of joint dysfunction, neurological interference, and adaptive strain. It is far more than a bone that has slipped out of place. It is a living, shifting pattern that changes how the body manages its energy and how the brain and body stay in communication.

What Chiropractors Mean by Spinal Subluxation

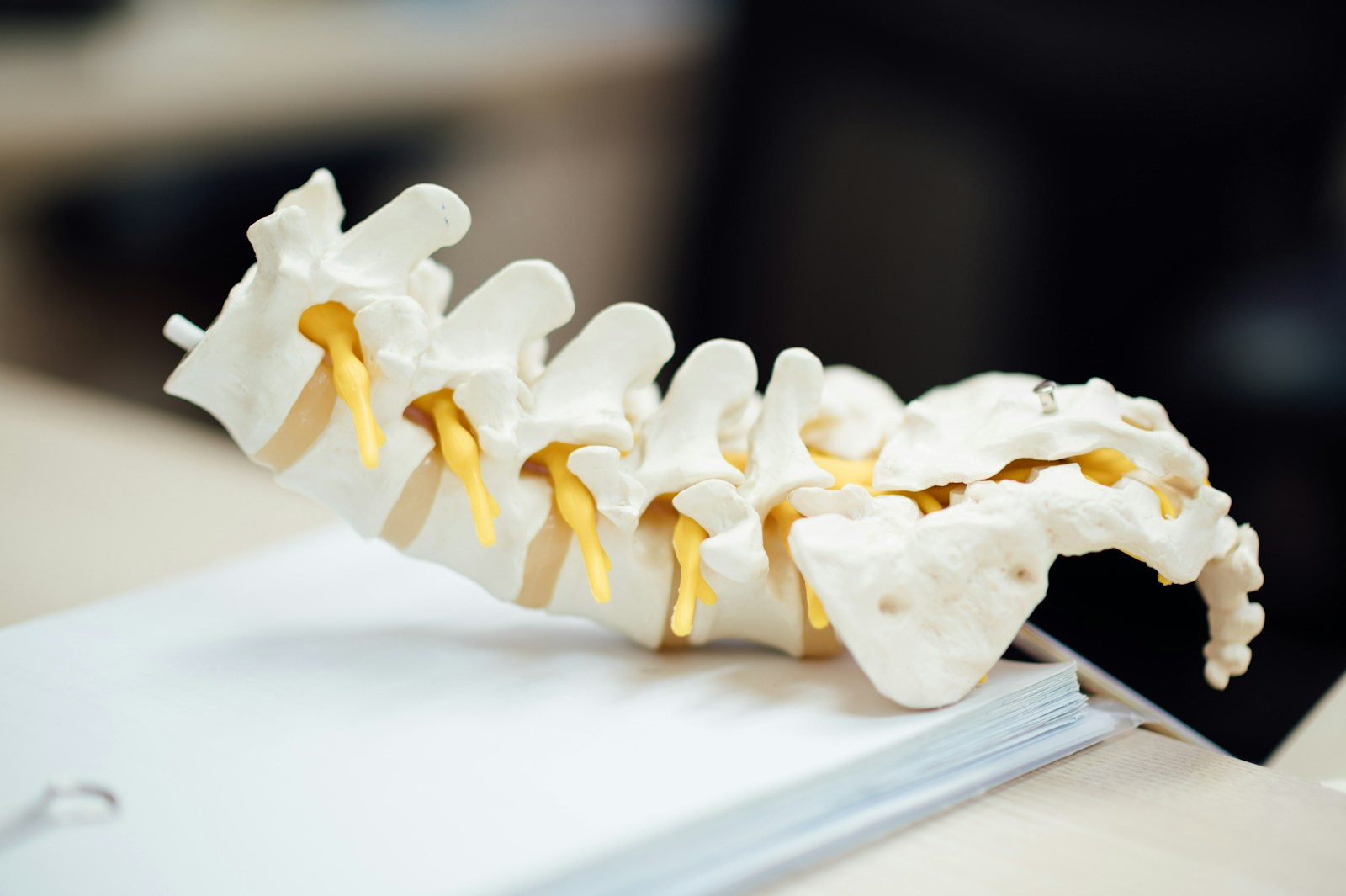

Inside the profession, the word spinal subluxation carries much more than a single dictionary definition. Chiropractors use it to describe a pattern in the spinal column where one or more spinal vertebrae are not moving or stabilizing the way they should, and that mechanical disturbance is coupled with changes in nerve signaling. It is not simply a question of whether a vertebra is a millimeter off center on an x-ray. It is whether that vertebral subluxation is altering how the brain senses and controls the body.

Over the years, many in the chiropractic profession have refined how we talk about subluxation. The concept has grown from a simple “bone out of place” idea into a model that includes joint dysfunction, altered muscle recruitment, changes in autonomic tone, and the way all of that may influence organ system function and general health. When we speak of vertebral subluxations today, we are speaking about a functional, neurological situation that is happening at the joint surfaces and within the spinal cord and spinal nerves at the same time. In that sense, the subluxation construct is one of the most important clinical ideas we work with.

The Chiropractic Definition of Subluxation

Within certain schools of chiropractic teaching, the definition of subluxation usually begins at the joints. A vertebra is not moving properly in relation to its neighbors, the joint surfaces are not sharing load the way they should, and the surrounding soft tissue adapts with postural tension and guarding. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges and various national chiropractic associations often describe this as pathological articular changes that compromise neural integrity. In plain terms, articular changes that compromise neural signaling of [position and motion can shape how the nervous system receives and sends information and may influence nerve system function and impact general health.

From there, the model expands into what many of us learned as the vertebral subluxation complex. The VSC recognizes that vertebral subluxation is not a single event, but a pattern that involves biomechanics, inflammation, spinal muscles, and autonomic control. This is why subluxations can cause more than localized discomfort. Subluxations can also cause shifts in energy, coordination, and stress handling. Chiropractic is concerned with the preservation and restoration of health at the system level, not simply the reduction of local symptoms.

Vertebral Subluxation Versus Medical Subluxation

Outside chiropractic, the word “subluxation” usually means something quite different. In the medical setting, a spinal subluxation refers to a partial dislocation of a joint, often following significant trauma, and it is typically seen clearly on imaging like an x-ray or MRI. That medical use of the term is about structural displacement. The chiropractic subluxation, and especially the vertebral subluxation complex, is a functional construct. It focuses on how vertebral misalignment and restriction relate to nerve roots, the spinal nerve, and the spinal cord, whether or not there is a dramatic dislocation.

This difference in language has fueled part of the long-standing discussion around subluxation in chiropractic in the United States and elsewhere. Critics sometimes look for the medical version of a subluxation and conclude that the chiropractic subluxation cannot be real if it is not always visible as a large shift in the spinal vertebrae. Chiropractors, on the other hand, are observing joint dysfunction, altered muscle patterns, autonomic imbalance, and changes in clinical traits that all point to a vertebral subluxation with neurological consequences, even when the spinal column looks relatively normal on film.

Why Definition Matters for Modern Practice

For a neurologically focused chiropractor, being precise about what we mean by spinal subluxation is not just an academic exercise. It shapes how we examine, how we adjust, and how we explain our care to patients who think chiropractic is based only on fixing neck pain or pain in the back. When you describe subluxation as a dynamic pattern of joint dysfunction and neural interference, it becomes natural to reach for technologies that can measure those changes over time. This is where full spine nerve system scans and other forms of neurological analysis belong in the everyday practice of chiropractic.

How Subluxations Develop: Understanding Etiology Through a Neurological Lens

Every chiropractor knows that vertebral subluxation does not appear out of thin air. There is always an etiology, often a layered history that starts long before the patient ever lands on your table. When you look at spinal subluxation through a neurological lens, you begin to see patterns of joint dysfunction, muscle guarding, and autonomic imbalance that have been building quietly for months or years. The person in front of you is not just dealing with one bad lift or one long car ride. They are living with the end result of how well, or how poorly, their nervous system has adapted to life’s physical, chemical, and emotional stress over time.

Spinal subluxations develop when the spinal vertebrae and surrounding soft tissue are asked to do more than they are designed for, more often than they can recover from. Sometimes that overload is obvious and dramatic, as in a collision or fall. Other times it is subtle and cumulative, such as hours of forward head posture at a screen, or months of sleeping in a twisted position. In both cases, the same basic story is unfolding: the spine is forced into compromised mechanics, the spinal muscles respond with postural tension and guarding, and the nervous system reorganizes itself around that pattern. Over time, subluxation refers to that persistent, maladaptive configuration of the spinal column and the neural control systems wrapped around it.

Common Causes of Spinal Subluxation

When we talk with patients about the common causes of spinal subluxation, it helps to think in three broad categories: macro-trauma, micro-trauma, and neurological distress. Each category can load the system in a different way, but they all converge on the same outcome: changes in joint function and changes that compromise neural integrity. Some of the most frequent physical stressors you see in daily practice include:

- Macro-trauma: Falls, sports impacts, and motor vehicle collisions that overload joint surfaces and ligaments in a single moment.

- Micro-trauma: Repetitive motions at work, unilateral carrying (bags, kids, tools), and long-term postural distortions that slowly deform the spinal column.

- Developmental or growth stresses: Rapid growth spurts in adolescents, or long-standing asymmetries and compensations from earlier injuries.

Beyond the purely mechanical, many of the most powerful drivers of vertebral subluxation live in the biochemical and emotional realms. Early exposure to antibiotics and other environmental toxins, disrupted sleep, poor nutrition, and sedentary habits all create a background load for the body to manage. Add to that chronic worry, frustration, and fear, and you have the perfect setup for sympathetic overdrive. Subconsciously, the body braces. Spinal muscles tighten, breathing shifts, spinal nerves become more sensitive to compression and stretch, and subluxations can also cause a wide range of traits and signs that extend beyond the local spinal region. This is where the etiology of subluxation and dysautonomia begin to overlap.

Over time, these repeated stress inputs can progress well beyond simple stiffness or temporary joint dysfunction. Subluxations can cause abnormal wear on joint cartilage and discs, leading to degeneration and altered mechanics through long segments of the spinal column. They may influence how nerve roots exit, how spinal nerves conduct, and how the spinal cord processes incoming information. In that sense, spinal subluxations are not just about one misaligned vertebra. They are about how the entire system has adapted to keep the person upright and functional. As neurologically focused doctors of chiropractic, our work is to understand that etiology clearly, then use precise chiropractic adjustment and objective analysis to help the body reorganize toward better performance.

Learn more about INSiGHT scanning?

Fill this out and we’ll get in touch!

"*" indicates required fields

Signs and Symptoms: What Subluxations Can Present Like in Practice

In daily practice, spinal subluxation rarely walks in and introduces itself by name. It shows up as the busy parent who cannot turn their head fully to shoulder check. It shows up as the athlete whose low back tightens every time they increase their training load. It shows up as the child who seems restless, clumsy, or always “out of sorts.” These are the real-world signs and symptoms of vertebral subluxation that chiropractors see all day long, long before a report mentions degeneration or a disc problem. The art is learning to recognize when these traits are simply short-term reactions and when they represent a deeper, ongoing pattern of joint dysfunction and neurological interference.

When vertebral subluxations develop, they do not just affect one structure. Joint surfaces lose their smooth, coordinated movement, spinal muscles change their tone, and soft tissue around the segment begins to compensate. Subluxations can cause local irritation at the level of the spinal nerve and nerve roots, but they can also set up broader patterns in posture and autonomic tone that reach far beyond the original level. This is why a single spinal subluxation can present with local discomfort in the neck, yet show up as widespread postural tension or even altered sleep and energy when you look more closely at the person’s overall system function.

Local Signs You See Every Day

Most chiropractors first encounter spinal subluxations through the classic, local traits that bring people into the office. Patients tend to describe these changes in simple language, even when the underlying neurophysiology is complex. Some of the most common local expressions include:

- Neck pain and pain in the back: Often aggravated by movement, prolonged sitting, or sustained postures. The intensity may fluctuate, but the pattern tends to recur because the underlying joint dysfunction has not been fully addressed.

- Restricted mobility: Difficulty bending, rotating, or extending through a spinal region. Patients talk about feeling “stuck” or “locked up,” especially first thing in the morning or after static postures.

- Local tenderness and soft tissue changes: Palpable tightness, nodularity, or guarding around a suspicious segment, reflecting how subluxations may cause muscle guarding and protective responses.

These local signs are important, but they are only one layer. By the time a person’s neck pain has become chronic, their spinal column has usually been compensating for quite some time. Spinal subluxations can also cause patterns of asymmetry and imbalance that you can see and feel: a head that consistently tilts to one side, a shoulder that is always high, or a pelvis that never quite levels, even after stretching. Underneath those visible changes, the spinal muscles are working much harder than they should just to maintain upright posture.

Neurological Traits Beyond the Local Site

Because vertebral subluxation is a neurological as well as mechanical event, the traits you observe often extend well beyond the immediate area of complaint. Irritation or compression around a spinal nerve can create numbness, tingling, or burning that travels along a dermatome. Irritation at the upper cervical spine can contribute to tension-type headaches. Dysautonomia in the thoracic region can influence breathing patterns and energy levels. In practice, you will often hear patients describe:

- Recurrent headaches or a feeling of pressure at the base of the skull.

- A tendency toward poor sleep or waking unrefreshed, even when they spend enough hours in bed.

- Episodic numbness or “pins and needles” into the arms or legs, particularly with certain positions.

Viewed through the traditional lens, these might simply be labeled symptoms and managed one by one. Viewed through the lens of spinal subluxation, they become a pattern that suggests changes that compromise neural integrity. This is where neurological scanning has such value. Surface EMG can show how spinal muscles are overworking or underworking around those regions, and surface electromyographic scanning has demonstrated good reliability in documenting these patterns. Thermal scanning can reveal asymmetries that match the person’s traits. Heart rate variability can show whether their autonomic system is robust and adaptable, or whether it is living in a chronic state of sympathetic overdrive.

Progressive Changes When Subluxations Are Left Unaddressed

If vertebral subluxations remain unaddressed for months or years, the signs and symptoms often shift from transient episodes to more persistent patterns. Joint surfaces that were once simply restricted can begin to show visible degeneration. A disc that has been overloaded for years may develop bulging or thinning. Spinal muscles that have been compensating chronically may become fatigued and weak in some regions, hypertonic and shortened in others. The person might not always connect these changes to spinal subluxation, but you can see the through line when you place their history, exam findings, and scan views side by side.

For the modern chiropractor, the key is not to reduce all of this to a single symptom such as neck pain. It is to recognize that a spinal subluxation is a living, evolving story. The local traits, the broader neurological signs, the emerging degenerative changes, and the adaptive patterns in posture and muscle activity all point back to the same central issue: the nervous system is working around a problem instead of through it. By identifying those patterns clearly, documenting them with objective measures, and tracking how they change under chiropractic care, you help patients understand that you are not simply chasing pain in the back. You are helping their system move toward a more efficient, resilient way of managing life.

Inside the Vertebral Subluxation Complex (VSC)

Once you accept that a spinal subluxation is more than a single vertebra that looks a little off on an x-ray, you are already stepping into the territory of the vertebral subluxation complex. The VSC is our way, as chiropractors, of admitting that this is not a one-dimensional finding. It is a cluster of related changes involving joint dysfunction, spinal muscles, the spinal cord and spinal nerves, and the way the brain regulates organ system function. When you explain it this way to a patient, you move from talking about a bone that slipped to a story about how their whole system is coordinating movement, energy, and adaptation.

At its heart, the vertebral subluxation complex recognizes that vertebral misalignment is only one piece of the puzzle. A spinal segment can be slightly misaligned but still resilient if it moves well, loads evenly, and communicates clearly with the nervous system. It becomes a vertebral subluxation when that subtle vertebral misalignment is coupled with faulty motion, abnormal loading of the joint surfaces, and altered neural signaling. The surrounding soft tissue and spinal muscles adapt to this new reality, and over time the nervous system rewrites how it manages that region. This is why subluxation is best understood as a complex, not a single static event, and why models of vertebral subluxation have been proposed that integrate biomechanics and neurophysiology.

The Components of the Vertebral Subluxation Complex

Different chiropractic texts describe the vertebral subluxation complex in slightly different terms, but they all agree on the same broad elements. You can think in terms of five core components that you are assessing every time you examine a spine:

- Biomechanical component: Restricted or aberrant motion at a spinal segment, altered joint play, and abnormal loading patterns in the spinal column. This is where joint dysfunction lives.

- Neurological component: Irritation, stretch, or altered afferent input at the level of the spinal nerve, nerve roots, and spinal cord. This is where changes that compromise neural integrity begin.

- Muscular component: Changes in spinal muscles, from postural tension and guarding to fatigue and weakness, that reflect how the body is trying to stabilize the affected spinal region.

- Inflammatory and soft tissue component: Involvement of ligaments, joint capsules, and surrounding soft tissue that can further limit motion and feed nociceptive input back into the nervous system.

- Autonomic and systemic component: Shifts in autonomic balance that may influence organ system function and general health, especially when subluxations become long-standing.

When you step back and look at these components together, the vertebral subluxation complex stops looking like a simple local problem and starts looking like a regional or whole-body pattern. The person does not just have a stiff spinal segment. They have a nervous system that has reorganized itself around that segment, often in the direction of sympathetic overdrive and reduced adaptability. This is exactly why a vitalistic chiropractor who thinks in terms of system function is so interested in documenting not just structure, but function.

From Joint Dysfunction to Neural and Systemic Impact

In practical terms, the VSC describes how a small mechanical problem can become a larger neurological situation. A restricted facet joint begins as a local issue. Left unaddressed, it can change how that segment moves with its neighbors, altering the biomechanics of an entire spinal region. The altered mechanics change the afferent input the spinal cord receives from that area. This new input shifts how the central nervous system perceives the trunk, limbs, and even internal organs connected through those segments. Over time, what started as joint dysfunction can affect balance, coordination, respiratory patterns, and stress chemistry.

This is where the clinical meaningfulness of subluxation becomes easier to see. You can palpate the fixation and see the altered posture, but you can also measure how the nervous system is handling the burden. Surface EMG shows how much extra effort the spinal muscles are spending to hold the body up. Thermal scanning reveals areas where autonomic control of blood flow has become lopsided. Heart rate variability shows whether the person’s overall adaptive capacity is robust or depleted. These neurological scans do not replace your hands. They give you a three-dimensional view of the vertebral subluxation complex and how deeply it has woven itself into the patient’s system.

For the modern chiropractor, the VSC is not just a teaching model. It is a practical framework that guides examination, care planning, and progress evaluations. When you explain to a patient that their spinal subluxation is affecting both their structure and their system function, and then show them scan views that match that story, they begin to understand why a single quick visit is not a complete solution. They see that correcting vertebral subluxation is about helping the nervous system reorganize out of a long-standing pattern, step by step, and that is a process you can observe, measure, and celebrate as their scans and their life both begin to change.

How Chiropractors Evaluate Subluxations Today

If there is one place where the rubber meets the road in the practice of chiropractic, it is the evaluation. Every chiropractor has felt the difference between a spine in disorder and a spine in flow. You can palpate it. You can see it in posture. You can hear it in how a person describes their energy, their sleep, or their recurring tension. But as the profession continues to evolve, the way we evaluate spinal subluxation has expanded well beyond static listings or structural snapshots. Modern chiropractors blend traditional hands-on assessment with functional and neurological analysis to fully understand what the vertebral subluxation complex is doing inside the body.

Traditional components of the evaluation still matter deeply: history, postural inspection, motion palpation, and orthopedic or neurological testing. These help you identify where joint dysfunction may be playing a role, and they reveal patterns that the person may have normalized for years. But these tests alone capture only part of the story. They are excellent at identifying how the joint surfaces are behaving, whether inflammation is present, and where the person feels symptoms. They often fall short when it comes to identifying the underlying changes that compromise neural integrity and affect system function and general health.

The Role of X-ray and Structural Imaging

X-rays remain a valuable tool because they help clarify the structural environment in which a spinal subluxation lives. They reveal degenerative changes, vertebral misalignment, disc thinning, congenital variations, or pathological findings that may influence care. But one of the biggest misunderstandings outside our profession is the assumption that x-ray alone should reveal a subluxation. Medical definitions of spinal subluxation require a visible dislocation; chiropractic subluxation does not. If you rely solely on x-ray to detect vertebral subluxations, you overlook the functional and neurological components that define the VSC.

This is why chiropractors use x-ray responsibly as part of a whole-person examination. Structural imaging helps rule out contraindications, clarify the integrity of joint surfaces, and guide certain aspects of chiropractic adjustment technique. But it cannot measure dysautonomia, postural tension, or adaptive strain. For that, you need tools that read the nervous system directly.

Neurological Scanning: The Modern Standard for Detecting and Tracking Subluxations

To understand spinal subluxation in a meaningful, measurable way, you must be able to see what the nervous system is doing. That has always been the challenge. Chiropractors could feel joint dysfunction and observe postural distortion, but we could not objectively quantify dysautonomia or adaptive capacity without technology. Today, neurological scanning fills that gap. It allows chiropractors to monitor the mechanical, muscular, and autonomic components of the VSC with precision and reproducibility. It anchors the conversation in measurable system function rather than subjective symptom reports.

This is where the INSiGHT neuroTECH and Synapse software have helped revolutionize the practice of chiropractic. Instead of relying on a single lens, INSiGHT instruments provide a three-dimensional analysis of how a person is adapting, compensating, and responding to neurological distress. These scans do not replace your hands or your expertise as a doctor of chiropractic. They enhance it. They anchor your interpretation in data that patients can see and understand, and they help you communicate the clinical meaningfulness of subluxation without getting stuck in arguments about dogma or science.

The neuroCORE: Measuring Motor System Energy

Surface EMG has long been recognized as a reliable tool for evaluating spinal muscles and neuromuscular activity in research and clinical settings. The INSiGHT neuroCORE takes that foundation and delivers a clear, color-coded picture of energy imbalance along the spinal column. Hypertonicity, hypotonicity, asymmetry, and compensation patterns become instantly visible. You see whether the person’s spinal muscles are working far harder than necessary simply to hold them upright. In the language of the VSC, this reveals the muscular and biomechanical components of vertebral subluxation and how deeply they are influencing the system.

The neuroTHERMAL: Mapping Autonomic Patterning

Paraspinal thermography is one of the most powerful, non-invasive tools for detecting dysautonomia. The INSiGHT neuroTHERMAL measures temperature asymmetries with extraordinary precision, identifying crescendo patterns, clumping, bilateral cooling, and other indicators of sympathetic imbalance. These findings speak directly to the autonomic component of the vertebral subluxation complex. When a patient sees red and blue patterns along their spine, they understand instantly that something deeper than joint stiffness is occurring. Thermography helps them see neurological distress instead of just feeling symptoms.

The neuroPULSE: Assessing Adaptive Capacity

Heart rate variability measurement has become a widely recognized method for assessing autonomic balance and recovery potential, and neurophysiology work on the spinal cord supports the idea that spinal influences can affect broader regulation. The neuroPULSE expresses HRV in a way that chiropractors can teach and patients can grasp. By displaying autonomic balance on the horizontal axis and overall adaptive reserve on the vertical axis, the Rainbow graph places each patient into one of several distinct zones. Most new patients arrive in the lower left quadrant – sympathetic dominant with diminished reserve. As chiropractic adjustments reduce neurological interference, many move upward and rightward toward the green zone, which represents a better adapted nervous system.

Synapse Software and the CORESCORE

INSiGHT’s Synapse software weaves all three technologies together into a single, easy-to-understand metric called the CORESCORE. This neural efficiency index allows chiropractors to track how system function is changing across time. It also provides scan views that communicate why a care plan is necessary, how the body is adapting, and where progress is occurring. Importantly, Synapse does not produce care plans. It provides objective data that chiropractors use to design customized plans that reflect the unique needs of each patient. When patients see these reports, they stop focusing on visits and start valuing results.

Chiropractic Care for Vertebral Subluxation: What Chiropractors Use and Why It Works

The chiropractic adjustment remains the signature intervention within the practice of chiropractic, but its purpose is often misunderstood outside the profession. Many still believe chiropractic adjustment exists to crack tight joints or relieve temporary symptoms. But when viewed through the lens of the vertebral subluxation complex, a spinal adjustment is a precise neurological input used to restore proper motion, reduce mechanical and autonomic stress, and improve system-wide coordination.

When joint dysfunction persists, afferent input from the spinal region becomes distorted. The central nervous system reorganizes itself around this abnormal feedback, affecting spinal muscles, autonomic tone, and even higher centers involved in motor control and emotional regulation. A chiropractic adjustment interrupts this maladaptive loop. It introduces a corrective force that stimulates mechanoreceptors, normalizes spinal movement, and allows the spinal cord to reprocess information more accurately.

Building a Care Plan Through a Neurological Lens

A care plan for vertebral subluxation should be based on how deeply the subluxation has affected the patient’s system – not simply on symptom intensity. While someone may arrive reporting neck pain or numbness, their scans may reveal long-standing dysautonomia, asymmetry, or exhaustion. This is why neurologically based care often begins with more frequent visits, followed by a gradual transition into stabilization and then long-term wellness. The goal is not just relief. It is restoration and preservation of nervous system performance and spinal health.

Spinal subluxation has always been at the core of chiropractic, but how we understand it – and how we communicate it – has evolved. Chiropractors today stand at the intersection of tradition and technology. Our roots are in hands-on adjusting, innate intelligence, and the belief that the body heals best when its nervous system is free from interference. Our present and future are built on objective data, functional analysis, and the ability to measure what is happening beneath the surface.

As we move deeper into the neuro-age of chiropractic, we have the opportunity to define vertebral subluxation not as a point of controversy but as a clinically meaningful, measurable pattern that influences how people adapt to stress. With the help of full spine nerve system scans, surface EMG, thermography, and HRV, chiropractors can demonstrate the reality of subluxation in ways that resonate with modern patients and healthcare colleagues alike. The widespread assertion of the clinical meaningfulness of subluxation is being refined by careful measurement and better communication.