If you have been in practice for any length of time, you have met the patient who walks in, rubs the back of their head, and says, “It feels like someone is zapping me right here.” The symptoms might shoot from the upper neck into the scalp, sometimes toward one eye. They have tried migraine medications, muscle relaxants, or just “pushing through it,” yet the episodes keep coming back. Somewhere in that story, the occipital nerve is usually involved.

The occipital nerve system is a group of sensory branches in the upper cervical region that carry messages from the back of the head and upper neck into the brain. When these nerves are calm and free of unnecessary tension, the scalp and upper neck simply report normal sensation. When they are irritated or compressed, those same nerves can trigger a very distinctive pattern of symptoms often called occipital neuralgia. For many people, this shows up as sharp, stabbing, electric shock sensations at the base of the skull or in the posterior part of the scalp. For the chiropractor, it is a powerful reminder that the upper cervical spine is more than bones and joints. It is a high-traffic crossroad of spinal nerves and sensitive neural pathways.

In a traditional model, the focus often lands on managing the headache label. Is it migraine, tension, cluster, or occipital neuralgia. From a neurologically focused chiropractic perspective, the more important question is: what is happening to the nerves that serve the head and neck, and how well is this person’s nervous system adapting to stress. That is where a nerve-first approach, supported by INSiGHT scanning technology, changes the story. Instead of chasing symptoms, we start asking how reserve, energy use, and autonomic regulation are influencing the occipital region.

What Is the Occipital Nerve?

The term “occipital nerve” actually refers to a small family of nerves that live at the junction of the head and neck. These are sensory branches of the upper cervical spinal nerves that carry information from the back of the scalp and upper neck into the central nervous system. In simple terms, the occipital nerve network is how the brain listens to what is happening along the back of your head, near the occipital region, and just below it. When those nerves send clear, appropriate messages, the scalp simply feels normal. When those same pathways are irritated, compressed, or inflamed, they can generate a very distinct pattern of head and neck symptoms.

From an anatomical standpoint, the occipital nerve group includes the greater occipital nerve, the lesser occipital nerve, and the third occipital nerve. Each nerve that arises from the upper cervical levels follows its own path through muscle, fascia, and connective tissue before it emerges into the scalp. Along the way, these nerves pass near joints, ligaments, and vascular structures that can become a potential source of nerve compression when there is chronic mechanical stress or neurological distress. That is why upper cervical alignment, posture, and nervous system performance matter so much when you are evaluating someone with occipital region symptoms.

Even though the occipital nerve system is often discussed in the context of occipital neuralgia, it is important to remember that its primary role is to transmit sensation, not symptoms. These are sensory spinal nerves, not pain nerves. They carry all kinds of information to the brain, from light touch and pressure to uncomfortable signals when tissues are irritated. The brain then decides how to interpret those incoming messages. When irritation becomes ongoing, the brain can start to register those signals as persistent aching, burning, or even stabbing pain in the posterior part of the scalp.

For the chiropractor, it is useful to picture the occipital nerve network as the “reporting line” for the back of the head and upper neck. The nerve supplies sensation to the scalp, but it lives in the same neighbourhood as the upper cervical joints, the suboccipital muscles, and the soft tissues that often show postural tension in stressed patients. When you see a cluster of head or neck pain focused at the base of the skull, it is an invitation to ask how that region is functioning as part of the broader nervous system. Is there excessive nerve tension from poor posture. Is there irritation at the level of the cervical nerve roots. Is the entire system living in sympathetic overdrive.

- The occipital nerve group is made up of three main branches that arise from the upper cervical spinal nerves.

- These nerves carry sensory information from the occipital region of the scalp and upper neck into the brain.

- Irritation along their course can lead to symptoms described as occipital headache or occipital neuralgia.

- Mechanical stress, posture, and overall nervous system performance all influence how these nerves behave.

The Three Main Branches: Greater, Lesser, and Third Occipital Nerves

When we talk about the occipital nerve in practice, we are usually talking about three distinct branches that arise from the upper cervical spine and then fan out into the scalp. Each nerve that arises from this region passes through layers of muscle and connective tissue before it reaches the surface. Along the way, it interacts with the joints, ligaments, and vascular structures that chiropractors examine every day. Together, these branches create a sensory map for the back of the head and upper neck, and each nerve supplies its own piece of that map.

The greater occipital nerve, sometimes called the great occipital nerve, is the biggest purely afferent nerve that arises from the dorsal ramus of the C2 spinal nerve, often with a contribution from C3. Many texts describe it as the biggest purely afferent nerve in the cervical region. After branching from the upper cervical spinal nerves, it travels upward between deep suboccipital muscles and then pierces the muscular and fascial layers near the external occipital protuberance. In this region, the GON and the occipital artery often run close together, with the nerve typically found just lateral to the occipital artery. From there, it spreads out over the scalp, and the distribution of the greater occipital nerve reaches from the lower occipital region up toward the vertex of the skull.

This is the branch that most chiropractors think of first when they hear the term occipital neuralgia. When there is chronic joint irritation, mechanical stress, or sustained postural tension around the C2 segment, it is easy to see how compression of the greater occipital nerve could occur where it passes through tight musculature near the occipital protuberance. For patients who describe symptoms that start at the base of the skull and then climb up the back of the head, the path of the greater occipital nerve gives you a very clear anatomical explanation.

The lesser occipital nerve has a different origin and territory. It is typically formed from the ventral rami of C2 and C3 spinal nerves as part of the cervical plexus. After leaving the cervical nerve roots, it runs upward along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle toward the mastoid region. The lesser occipital nerve supplies sensation to the lateral scalp, the upper portion of the auricle, and the area just behind the ear. In this zone, it travels near other sensory branches such as the greater auricular nerve and, more anteriorly, the supraorbital nerve. When a patient describes pain originating behind the ear or along the side of the head, it is often the lesser occipital nerve that is reporting distress.

The third occipital nerve arises from the dorsal ramus of C3 and is sometimes described as a mixed nerve because it carries both sensory and small motor components. In the context of head and neck symptoms, its sensory role is the most clinically relevant. This nerve wraps around the lower occiput, coursing near the occipital protuberance and the mastoid region, and innervates the skin over the lower occipital area and upper neck. The nerve and the third occipital branch are frequently involved when the C2–C3 facet joint is irritated, such as after whiplash or repetitive microtrauma. Patients may report localized pain in the posterior area of the lower skull that feels sharp or stabbing when that segment is stressed.

- The greater occipital nerve is a large sensory branch from the C2 spinal nerve that travels near the occipital artery and supplies most of the posterior scalp.

- The lesser occipital nerve comes from the cervical plexus at C2 and C3 spinal nerves and serves the lateral scalp and tissue around the ear.

- The third occipital nerve branches from C3 cervical nerve roots and innervates the lower occipital region and upper neck.

- Understanding where each nerve divides and what territory it supplies helps you match a patient’s symptom pattern to specific cervical spinal nerves and upper cervical segments.

Occipital Neuralgia: When the Occipital Nerve Becomes a Source of Symptoms

When the occipital nerve network becomes irritated or compressed, the symptom picture often shifts from a general head or neck complaint into something much more specific. This is where the term occipital neuralgia enters the conversation. In formal classifications, occipital neuralgia is a type of headache characterized by episodes of paroxysmal shooting or stabbing pain in the posterior area of the head, typically following the distribution of the greater occipital nerve.

Clinically, the hallmark of occipital neuralgia is neuralgia pain that feels sharp, electric, or shock-like. Patients often describe it as a lightning bolt or a live wire at the base of the skull. These paroxysmal shooting or stabbing pain episodes may start in the upper neck or near the occipital protuberance and then radiate up the scalp. For some, the stabbing pain in the posterior head travels forward toward one eye, which is why occipital neuralgia can be confused with migraine or other head and neck syndromes. Between attacks, there may be a dull ache or sense of heaviness in the occipital region, so the symptom picture can appear mixed, and a contemporary occipital neuralgia review in the neurology literature reflects this pattern.

It is important to note that occipital neuralgia is not simply any occipital headache. Many patients report pain from occipital regions that turns out to be muscle tension, cervicogenic headache, or migraine with occipital involvement. Occipital neuralgia usually follows a more specific pattern involving the greater occipital nerve or its neighboring branches. The involved segment is tender to touch along the course of the nerve, and light pressure may reproduce the same paroxysmal symptoms the patient experiences during a flare.

For chiropractors, this distinction matters. When a person presents with symptoms that sound like neuralgia pain rather than a diffuse headache, you are no longer just dealing with an irritated muscle or a stiff joint. You are looking at a sensory spinal nerve that has become hypersensitive, often in the context of chronic mechanical stress and neurological distress. Understanding where occipital neuralgia fits within the broader family of headache disorders helps you communicate clearly with patients, collaborate effectively with other providers, and keep your focus on improving nervous system performance rather than chasing labels.

How Occipital Neuralgia Presents: Symptoms and Overlap with Other Headache Disorders

When the occipital nerve becomes irritated, the symptom pattern is usually quite different from a dull, global tension headache. People with occipital neuralgia often experience pain that starts at the upper neck or the base of the skull and then climbs up into the scalp. This is classic occipital headache territory. The neuralgia pain is frequently described as aching or burning at rest, with sudden, sharp or piercing bursts that feel like an electric shock. These episodes can be brief and intense or can flare repeatedly throughout the day, leaving the person drained and wary of moving their head.

The quality of the symptoms is one of your best clinical clues. Patients may report pain that feels throbbing at the back of the head, then suddenly shifts into paroxysmal neuralgia. They might say they experience pain when they turn the head a certain way, lay on a particular side, or press over the occipital protuberance. In some cases, the pain in the posterior part of the scalp radiates forward toward one eye, which can make it look and feel like a migraine headache. This is where the diagnostic waters get muddy, because patients with headache that predominantly affects the occipital region may not fit neatly into a single label.

There are also sensory changes that go beyond simple headache pain. The scalp can become incredibly sensitive; even resting the back of the head on a pillow or lightly touching the hair can provoke symptoms. Some people notice numbness or tingling along the distribution of the greater occipital nerve, while others feel a constant bruised sensation in the lower occipital region. For chiropractors, mapping exactly where the person feels occipital pain, and how it behaves with touch and movement, is essential to distinguishing occipital neuralgia from other type of headache patterns.

Occipital neuralgia does not exist in isolation from other disorders. Many patients with headache seen in neurology or pain clinics carry overlapping diagnoses such as migraine or cluster headache. These conditions can be associated with occipital neuralgia or can inflame the occipital nerve secondarily. In practice, that means someone may report pain originating in the back of the head, along with light sensitivity, nausea, or other migraine features. Your job is not to replace the neurologist, but to recognize when head or neck pain centered in the occipital region follows a neuralgia pattern and when it looks more like a broader central sensitization picture.

- Occipital neuralgia symptoms usually start in the upper neck or occipital region and radiate upward into the scalp.

- The pain symptoms are often described as aching or burning with sudden electric shock–like bursts of neuralgia pain.

- Scalp tenderness, allodynia, and numbness over the posterior scalp are common clinical findings.

- Because these symptoms overlap with migraine and other headache disorders, careful history and examination are essential for accurate interpretation.

What Causes Occipital Neuralgia? Mechanical and Systemic Contributors

When you start seeing a recurring pattern of sharp, shooting symptoms along the back of the head, it is natural to ask what is irritating the occipital nerve in the first place. In many people, the problem begins where the cervical nerves exit the spine and travel through the soft tissues of the upper neck. A spinal nerve that is already under mechanical load at the joint level can become much more sensitive when the surrounding muscles are tight, the posture is collapsed, or the nervous system is living in a chronic state of neurological distress.

One of the most common contributors described in the literature is a pinched nerve at the upper cervical levels, especially involving the C2 spinal nerve and C2 and C3 spinal nerves. Degenerative disc disease, joint arthritis, and other age related changes can narrow the spaces where these cervical nerve roots travel. When you combine that with facet joint irritation or a history of whiplash, you get a perfect storm for nerve compression along the path of the greater occipital nerve and the third occipital nerve. The person may not feel anything for years, then a small injury or postural shift tips the system over the edge.

There are also systemic factors that can change the way nerves behave. Metabolic conditions such as diabetes and gout can promote nerve damage and make sensory pathways more reactive. Vascular changes, including vasculitis or irritation around the occipital artery, may interact with nerves that lie lateral to the occipital artery in the upper neck. When the gon and the occipital artery share a tight space surrounded by tense musculature, it does not take much to create a potential source of nerve compression that feeds into occipital neuralgia pain.

Previous surgery or trauma in the occipital region can also be a factor. Scar tissue from procedures on the scalp or skull may entrap small sensory branches right where the nerve divides as it enters the scalp. Even simple lifestyle patterns can contribute. Hours spent in a forward head posture, shoulders hunched, eyes locked on screens, place a continuous demand on the upper cervical spine and surrounding musculature. Over time, that posture driven load can lead to occipital nerve irritation in someone who already has limited adaptive reserve.

The encouraging side of this story is that nerve damage heals or calms in many cases when the underlying mechanical and neurological factors are addressed. As cervical spinal nerves are given a more favorable environment and the nervous system is supported to handle day to day demands more efficiently, pain from occipital neuralgia often becomes less frequent and less intense. For chiropractors, that is a direct invitation to look beyond the label and ask what is driving the load on the occipital nerve throughout the spine and nervous system.

How Clinicians Diagnose Occipital Neuralgia

Occipital neuralgia can be tricky to diagnose because it lives in the overlap between neurology, headache medicine, and musculoskeletal care. There is no single test to diagnose occipital neuralgia that will neatly separate it from every other type of headache characterized by posterior symptoms. Instead, clinicians put the story together from the history, examination findings, and response to specific procedures such as nerve blocks.

The diagnostic process usually starts with careful questioning about the symptoms. Does the person experience paroxysmal stabbing pain in the posterior scalp that follows the path of the greater occipital nerve or the lesser occipital nerve. Do they notice electric shock sensations that shoot from the upper neck toward the top of the head or one eye. Are there particular head and neck positions that trigger or worsen the episodes. This level of detail matters when you are trying to decide whether the problem is mainly muscular, joint related, or arising from a sensitized sensory nerve.

On examination, clinicians palpate along the course of the occipital nerve branches, especially near the occipital protuberance and the mastoid region. A focal tender point that reproduces the person’s typical neuralgia pain is a strong clue that the occipital nerve and the third occipital nerve are involved. The scalp may be extremely sensitive to light touch, and the person may pull away when you press even lightly over the nerve. At the same time, it is important to rule out broader neurological issues, so many physicians will perform a full cranial nerve and motor exam.

A Neurologically Focused Chiropractic Lens on the Occipital Nerve

From a neurologically focused chiropractic perspective, the occipital nerve is not just a structure that needs numbing. It is part of a larger conversation about how the nervous system is adapting to daily demands. When someone presents with neuralgia pain in the posterior scalp, it is a signal that the protective pathways in the upper cervical spine are under strain. Rather than starting with the question, “How do we stop this pain,” we begin with, “What is this telling us about the person’s nervous system performance and adaptive capacity.”

The upper cervical spine is a critical hub where motion, posture, and sensory input converge. When the occipital nerve branches leaving the cervical nerves are continually irritated by joint fixation or postural collapse, they can become more reactive to otherwise normal inputs. That reactivity often shows up as pain symptoms in the occipital region. Over time, the body may recruit more and more muscular guarding to protect the area, which increases postural tension, compresses soft tissues around the nerve, and feeds the cycle of neuralgia. In this context, the nerve is not the problem; it is the messenger.

Gentle, targeted chiropractic adjustments, applied within a thoughtful care plan, aim to improve joint motion, reduce mechanical irritation at the level of the spinal nerve, and normalize the way the brain receives information from the head and neck region. The goal is not to chase a single type of headache characterized as occipital neuralgia, but to enhance the person’s capacity to recover from neurological distress. When the upper cervical spine moves more freely and the nervous system is not locked in sympathetic overdrive, the environment around the occipital nerve improves.

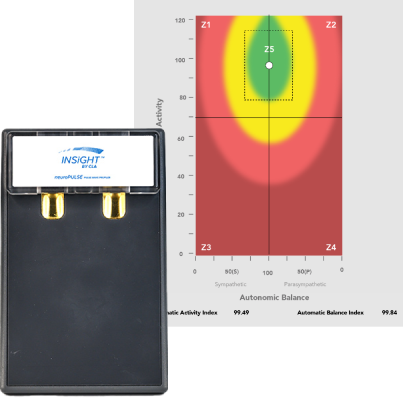

The RED model, which organizes findings into Reserve, Energy, and Dysregulation, gives you a practical way to think about these cases. Many patients with occipital neuralgia present with low reserve on HRV analysis, high energy expenditure in the spinal motor system due to chronic muscular guarding, and signs of autonomic dysregulation in the cervical region. This pattern involves the greater occipital nerve, the lesser occipital nerve, and the third occipital nerve, but it is driven by nervous system performance at a much broader level. Chiropractic care can be a powerful part of restoring coherence to this system, especially when guided by objective analysis rather than guesswork.

How INSiGHT Scanning Technology Helps Assess Patients with Occipital Region Symptoms

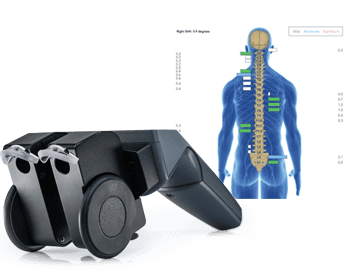

This is where INSiGHT neuroTECH and Synapse software truly shine for chiropractors dealing with occipital neuralgia and other occipital nerve related complaints. Neurological scanning allows you to move beyond “it hurts here” to “here is how your nervous system is processing and adapting.” Instead of relying solely on palpation and symptom description, you can show patients how their head and neck patterns fit into a complete neural profile.

The neuroCORE surface EMG instrument gives you an objective look at postural tension and energy use along the spinal region. In patients with occipital pain, you will often see elevated activity in the upper cervical muscles as they work overtime to protect irritated joints and nerves. As the neuroTECH analysis converts these signals into color coded bars, you can see how much extra energy the nervous system is spending just to hold the head upright. Over time, changes in these EMG patterns provide proof your care is making a difference by showing that the spinal motor system is no longer locked in protective overdrive.

The neuroTHERMAL instrument offers another layer of insight. Paraspinal thermal analysis in the cervical spine reveals temperature asymmetries that reflect changes in autonomic control of blood vessels. When you see persistent asymmetry or clumping patterns in the upper cervical region, it suggests that dysautonomia is part of the picture, not just mechanical irritation. Peer reviewed work on paraspinal thermography has documented its reliability and usefulness in assessing vertebral subluxation patterns, supporting its use as part of your objective analysis.

The neuroPULSE HRV instrument ties this local story into the bigger picture. By analyzing beat to beat variability, it assesses the balance and activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. Many patients with headache pain that includes occipital neuralgia plot in distressed or weakened zones on the Rainbow Graph, indicating low reserve and poor adaptability. Research shows that chiropractic care can measurably improve heart rate variability, reinforcing the idea that we are influencing more than symptoms alone.

Synapse software then pulls these separate analyses into a single CORESCORE, giving you and your patient a clear index of neural efficiency. The software’s scan views make the invisible visible by overlaying findings onto the spine, so the person can see exactly where their nervous system is struggling. You can show how the occipital region fits within a whole spine, whole system picture rather than treating it as an isolated “bad nerve.” As scans improve over time, that CORESCORE change becomes an easy to understand way to document that their nervous system status is shifting in a better direction, even as you continue to refine the care plan.

Integrating Findings into Care Planning and Collaboration

When you bring together a detailed history, a thorough upper cervical examination, and INSiGHT scanning data, you gain a level of certainty that is hard to achieve any other way. Instead of guessing why a patient is describing sharp occipital pain, you can point to specific findings: heightened EMG activity in the upper cervical spine, thermal asymmetries suggesting dysautonomia, and HRV analysis that shows limited adaptive reserve. That combination not only supports your clinical decisions, it also makes it much easier for the patient to understand why you are recommending a particular care plan.

Care planning for occipital neuralgia and occipital nerve related complaints should be realistic and transparent. It is important to explain that neuralgia usually behaves differently from a simple muscle strain. The goal is to reduce nerve tension and improve nervous system performance over time, not simply to chase symptom free days. As scans change and CORESCORE improves, you can show the person how their Reserve, Energy, and Dysregulation metrics are shifting, even if they still have occasional flares while the nervous system reorganizes.

Collaboration with other providers is another hallmark of a modern, nerve first practice. If imaging reveals significant compression of cervical nerve roots, or if the person has ongoing neurological deficits, referral to neurology or pain management specialists is appropriate. Having INSiGHT scan reports in hand during these conversations helps you demonstrate that you are monitoring objective neurological changes, not just collecting subjective reports. It also positions you as a valuable member of the team, focused on supporting spinal and nervous system function in a way that complements other treatment options.

For many patients, the most powerful experience is seeing their own progress on follow up scans. A series of four scan assessments over an initial phase of care lets you track how the nervous system is reorganizing. When a person who lives with long standing occipital neuralgia pain sees their EMG patterns normalize, their thermal asymmetries diminish, and their HRV move closer to a green zone of adaptability, they understand that care is about more than suppressing symptoms. It is about building resilience.

Bringing the Occipital Nerve Story Back to the Nervous System

The occipital nerve may seem like a small structure in a small region of the body, but for many people it becomes the site where years of mechanical stress, neurological distress, and limited adaptability finally speak up. Occipital neuralgia is a vivid reminder that when the nervous system is not handling load efficiently, the messages it sends can become sharp, persistent, and hard to ignore. As chiropractors, we have the privilege of listening to those messages and helping the body respond in a more resilient way.

Understanding the anatomy of the greater occipital nerve, the lesser occipital nerve, and the third occipital nerve gives you a clear map for matching symptom patterns to specific cervical segments. Recognizing how occipital neuralgia is a type of headache characterized by paroxysmal shooting and stabbing pain in the posterior scalp helps you distinguish it from migraine, cluster headache, and other headache disorders. Knowing the range of medical interventions, from occipital nerve block to occipital nerve stimulation, allows you to communicate effectively with other providers and guide your patients through their options without overstepping your role.

Most importantly, bringing the INSiGHT neuroTECH and Synapse ecosystem into this conversation lets you anchor that entire story in objective data. When you show a patient how their EMG, thermal, and HRV findings relate to their occipital symptoms, you help them see that the real work is not just quieting one nerve. The real work is improving nervous system performance so that the occipital nerve, and every other sensory pathway, can operate in a calmer, more adaptive environment.

In a world where headaches are often managed with quick fixes and labels, a neurologically focused, vitalistic approach stands out. You are not just adjusting vertebra and chasing pain. You are using advanced neurological scanning, clear communication, and consistent care planning to help people reclaim confidence in their bodies. The occipital nerve is simply one more pathway through which the nervous system tells its story. With the right tools and perspective, you can help your patients rewrite that story toward greater ease, adaptability, and long term performance.